The Rev. Anthony Bailey speaks to his multi-racial congregation in this undated photo provided by Parkdale United Church.

R

ev. Anthony Bailey stepped away from a whining megaphone and turned to address the crowd without it.

The Rev. Anthony Bailey speaks to his multi-racial congregation in this undated photo provided by Parkdale United Church.“I’m told I have a big mouth,” he remarked, as he stood in front of the Human Rights Monument near the Ottawa courthouse, where a vigil was being held for victims of a shooting a day earlier at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh.

Bailey sang “Hold on just a little while longer” for a few moments, as the crowd began to join in. He explained that the song allowed him to imagine a world without such violence. “We imagine and we see another world, and we live into that world with solidarity. That’s how everything is going to be alright,” he said.

Bailey is no stranger to violence and hatred. When he and his brother were attending CEGEP in Montreal decades ago, they were the target of a racially-motivated attack that killed Bailey’s brother.

Bailey explained that it was while he wrestled with the grief of his loss that he found his vocation. While Bailey was not seriously injured, this close encounter with death gave him the desire to find the purpose of his life so that he could live it fully.

“My feet are too short to outrun God, and I believe that God was pursuing me for this vocation,” he said.

96 hate crimes took place in the capital, a rate of attacks almost twice as high as other Canadian cities.

Bailey has led the congregation at the Parkdale United Church since 1999. The church stands at the corner of Parkdale and Gladstone, in Hintonburg, and provides spaces for church services and charity events.

However, this community has also experienced the pain of hatred first hand.

In January 2016, and again in November of the same year, the church was the target of racist graffiti. First on a wall and then on a door, the church was spray-painted with racist slurs, white supremacist slogans and swastikas.

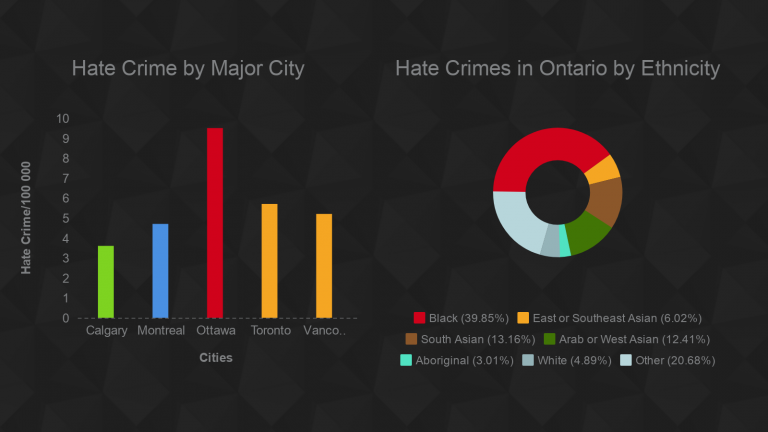

Such attacks are not uncommon in Ottawa. That same year, 96 hate crimes took place in the capital, a rate of attacks almost twice as high as in other large Canadian cities like Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver.

Hate crime can undermine trust and cohesion within a community. However, as in the case of the Parkdale United Church, pulling together in solidarity can make those bonds stronger.

Bailey explained that, following the attacks, the response was very clear. “We wanted to respond in a way that Jesus would have us respond, which was not to be hateful towards the other person or not to wish them the worst,” he said.

The Ottawa police helped them rebuild after the attack and have developed an ongoing relationship to strengthen each other. Bailey and the Ottawa police continue to work together today. He has even begun offering racial sensitivity training to new police recruits.

Lila Shibley, a constable in the Ottawa police Diversity and Race Relations section, was part of the response effort. She recalls that the attacks on the Parkdale United Church had been part of a series of such events that year. Mosques and synagogues had also been spray-painted with swastikas and racist messages. “It was a very precarious time for the community because a lot of these groups were being targeted just because the political climate was allowing that,” Shibley said, referring to the recent rise in racial tensions that some attributed to the U.S. election.

When the Parkdale United Church was vandalized, Shibley went to speak to Bailey. She wanted to make sure that the community would feel supported, and that the members and residents would know “if they needed anything from the police, that we would be able to provide that to make sure that the congregation felt safe.”

Shibley explained that attacks like the ones on the Parkdale church can have lasting impacts and need a sensitive response.

“It’s an attack on the entire community, and we recognize that,” she said.

Hate crimes by city and ethnicity. Ottawa is disproportionately represented in hate crimes, as are black victims, who represent around five per cent of the population but almost 40 per cent of victims.

The young man who spray-painted the church in November 2016 was only three weeks shy of 18 when he was arrested. Bailey said that the church was involved in having him tried as a juvenile rather than as an adult.

“If he was tried as an adult, he would have gone to jail, where he would have had little opportunity for rehabilitation,” he said. The young man was sentenced to community service, and he cleaned up the buildings he had defaced. Bailey met the young man after he was caught, and he said that the offender had since made a tremendous turn-around, though it came slowly.

When accepting an apology like the young man eventually offered in court, Bailey explained, “certainly you hope they’re being genuine but what I’m arguing, from a Christian perspective, our offering of forgiveness is not contingent on a person’s apology. It’s not contingent even on their remorse.”

Bailey says he strongly believes that forgiveness is an important part of recovering after an attack like the ones on Parkdale United Church. “Forgiveness is essential to being able to move forward in collaborative ways and restorative ways,” he said.

For Bailey, solidarity goes beyond faiths. The Parkdale United Church organized a blood drive in collaboration with Canada Blood Services, and Bailey coordinated an interfaith volunteer project with Habitat for Humanity where he “brought together a whole group from Bahà’i and Muslim and Jewish and Christian variety of spectrum to go together to build.”

Working across cultures and faiths is the essential part of how Bailey views the world. When he spoke in the cold afternoon at the October 28 vigil, it was not only to express sympathy for the Jewish community. Addressing the crowd gathered around the Human Rights Monument, he said, “Let your life be a light for reconciliation, for justice, and welcome, and love, and joy, and healing, and peace.”