O

h my God, this is actually happening,” Tina Regalbuto says as she watches the snow fall through the window of the downtown service where she is getting her fingerprints digitally scanned. Regalbuto’s been a convicted criminal for 25 years. The digital fingerprints are the start of her pardon process, and what she hopes will be a new life.

Because of a simple cannabis possession charge, she’s struggled to find work, go to school and travel. “It’s been hard to get a job above minimum wage,” she says.

Regalbuto getting her fingerprints digitally scanned. Sending those scans to the RCMP is the start of the pardon process.

Like the tens of thousands of Canadians with records like hers, she’s ready to start fresh.

October’s legalization of marijuana saw Minister of Public Safety Ralph Goodale announce that the government would move to pardon possession under 30 grams with “no further waiting period and no fee.”

Even though she’s long past the waiting period—anywhere from five to 10 years after the sentence is complete, depending on the conviction—she never thought about a pardon before. The application for a pardon normally carries a $631 fee when it’s filed with the Parole Board of Canada, and today’s fingerprinting costs her $84. With her struggle for work, she’s never had the funds before.

Regalbuto jumped at this new opportunity. Even though the pardon legislation hasn’t materialized yet, it can take months for the multi-step process to move forward before filing the actual application for record suspension with the Parole Board. She hopes by the time she’s done with the paperwork, the new law will be ready to go. If not, then she’s finally ready to pay for it herself. The recreational marijuana legislation convinced her it’s worth it either way.

The mindset of a teenager, the consequences of an adult

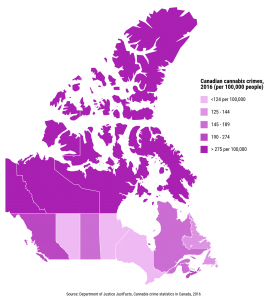

Some areas, mainly in northern Canada, are heavily affected by pot arrests. The ones convicted of simple possession will soon be eligible for immediate free pardons, according to the Liberals’ promise. Source: Department of Justice JustFacts, 2016

Regalbuto’s arrest happened just after her 18th birthday. “I really didn’t know what police were before then,” she says. “I met a guy who was a drug dealer and just lived the life. I was young and stupid. He was nine years older than me.”

One morning she woke up to a gun pointed at her by police searching her apartment. There was a gym bag with weed, magic mushrooms and a little bit of cocaine in it. There were 28 grams of weed on her dresser. The gym bag belonged to her boyfriend, she says, but the pot on the dresser and the apartment were hers. And she had cash on her, split up into two stacks. That, the police said, was proof of her dealing.

“It was split up because I’d set my rent aside,” Regalbuto says.

Her lawyer convinced her to plea to possession of the pot that was on her dresser. In exchange, the Crown dropped the trafficking charges. The judge gave her a summary conviction and a $75 fine with no jail time.

“I didn’t understand the greatness of it until I was older and needed to get a job that paid more than $12 an hour,” Regalbuto says.

An opportunity for housekeeping at $21 an hour came up at the Montfort Hospital, where she worked catering. It meant working around narcotics, and that meant a record check for her application. “So, I went down to the police station,” Regalbuto says.

That’s when she discovered the “greatness” of a conviction.

The officer handed her back her record sheet. He pointed out the conviction and expressed sympathy for Regalbuto, as what she was charged with wasn’t the law anymore. “I asked him if it could just go away,” she says.

Instead, the job opportunity went away.

A matter of basic fairness

Regalbuto fills out her pardon forms. The lengthy paperwork can be a barrier to completing the process, Jade Kulla of the John Howard Society says.

The pardon process is long. It starts with the prints, then the RCMP mails back the record associated with them. After that, it’s paperwork with the court, then more paperwork with every police jurisdiction she’s lived in for more than three months and then a form that asks her to make a statement on how her life would be better with a pardon. When Regalbuto sees that question, her eyes widen. “Duh!” she says.

Only then can she file the pardon application itself with the Parole Board of Canada. It was daunting and hard for her to understand.

She’s not alone. Jade Kulla, a spokesperson for the John Howard Society of Canada, a criminal justice reform group, says when people applying for a pardon find out it’s going to take time, “it usually breaks them a little, especially if they’re so eager to get it done.”

“They become helpless or no longer hopeful and they stop the process halfway through,” Kulla adds.

Kulla describes Regalbuto’s story as being typical of those who’ve tangled with the criminal legal system. “A simple charge or something that wasn’t necessarily a big deal has major effects throughout their life,” Kulla says.

Kulla says that jobs can be difficult to find, “even a cleaner at a grocery store.” Housing can be hard to find with more and more landlords needing record checks, and school can be a vicious circle with them trying to find the funds without jobs. “Stuff kind of piles up and it becomes difficult for them to continue on a normal path.”

Regalbuto has experienced every one of those issues for most of her life. “You grow up, you have kids, you try and go back to school, but to go back to school you need to get this job, you can’t get this career because it needs a clear record, you can’t get that career.”

Goodale’s announcement a month ago saw the government recognize that, calling it “a matter of basic fairness” that the government move forward with pardons when laws are changed.

Regalbuto doesn’t hold a grudge against the state that burdened her with what Goodale called a “stigma.”

“They can give me my life back,” Regalbuto says.

She already knows what she wants to do when the pardon comes through. “I want to go to Myrtle Beach with my parents and the rest of my family,” she says, describing the yearly frustration she’s felt as her parents take her children to South Carolina, while she can only go as far south as the border.

“I don’t want to be excluded anymore.”