A

dàwe. Pimisi. Zibi. These are words from the Algonquin language, but they also have something else in common. They are the names of recent public and private development projects in Ottawa. Projects that Dr. Lynn Gehl, an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe author, artist and Indigenous rights activist, describes as “little crumbs” compared to the bigger issue, the rights to their land.

Dr. Lynn Gehl, an Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe author, artist and Indigenous rights activist.

“It’s patronizing,” Gehl answered when asked about the use of her peoples’ language to name structures and developments. “I think it is embarrassing, humiliating and patronizing, that that’s what they’re offering us.”

Ottawa, along with about 48 million acres of eastern Ontario and southern Quebec, is situated on land that was never ceded by the Algonquin people that first lived here.

“These little crumbs that they’re giving us, such as naming streets and bridges and developments, in honour of our name,” said Gehl. “That’s not what we want, we want our land and resource rights back.”

Adàwe Crossing

The Adàwe crossing is a pedestrian and cycling bridge located over the Rideau River that connects Sandy Hill and Vanier. The word Adàwe means “to trade” in the Algonquin language. It was selected by the City of Ottawa after a six-month naming process that asked community groups surrounding the bridge to submit ideas and consulted with the Algonquins of Ontario organization.

“Naming is an important mechanism to ensure that the Indigenous history in our area lives on,” said Coun. Tobi Nussbaum of Rideau-Rockcliffe Ward who was involved with the naming process. “We thought it was extremely important to involve the Algonquins of Ontario early on in the process. Make sure they felt heard and listened to.”

The Algonquin organization represents 10 Algonquin communities in Ontario. However, Gehl points out that “Canada divided the Algonquins by the river, and language, religion and law,” and as such the Algonquin organization only represent Algonquin peoples living in Ontario, not Quebec.

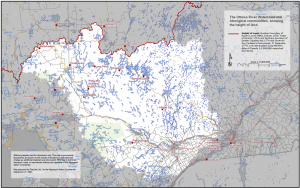

The Algonquin land claim consists of approximately 9 million acres of land in Ontario and 39 million in Quebec (shown in white). There are 10 communities represented by the Algonquins of Ontario, only one of which is a federally recognized Indigenous community – the Algonquins of Pikwakanagan. There are 9 federally recognized Algonquin communities in Quebec.

“When the City of Ottawa claims that they’ve negotiated with the Algonquins of Ontario, right there you have a problem,” she said. “They’re going along colonial divisions to make this claim that they’ve consulted with us.”

Perhaps more importantly, the Algonquins of Ontario organization is funded through grants from the federal and provincial governments. “You’re not really getting at a truth, you’re getting at a funded, skewed perspective for the purpose of somebody keeping their income,” said Gehl.

She describes this relationship as the Algonquins being put “in a vise,” but sympathizes with the decision makers as they negotiate land claim deals with the government through the modern treaty process. “I understand the tough situation that the chiefs are in, they have to make some practical decisions because they need some land for the community,” she said.

Pimisi LRT Station

Pimisi will be the new name for the former LeBreton Flats transit station when the Ottawa LRT opens next year. The city asked the Algonquins of Ontario organization to name the station as its location is close to Chaudière Falls – a sacred gathering place for the Algonquins. They chose the word Pimisi, which means “eel,” an animal that provided the Algonquin people with food, medicine and “spiritual inspiration.”

“The more, the merrier!” said Albert Dumont, an Algonquin poet, speaker and story teller. “The more Indigenous names there are, the more children might ask, ‘What does that word mean?’ or ‘Why is our street called this?’ and parents will want to be able to answer.”

Dumont sees the names as a chance to raise awareness of the Indigenous communities and a step towards reconciliation, “albeit in a small way,” he said.

When the Ottawa River Parkway was renamed in 2012, Dumont suggested the name Algonquin Parkway. It fell on deaf ears though and the National Capital Commission named the parkway after Sir John A. Macdonald, which Dumont calls “an offence to Indigenous peoples” because of Macdonald’s involvement in creating the residential schools.

The atrocities of the residential schools resulted in the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) which released its 94 “calls to action” in 2015. The City of Ottawa created its own Reconciliation Action Plan in February 2018 in solidarity with the TRC’S findings. The city works with local Indigenous groups to improve city services and support culture, health and education in Indigenous communities.

“Clearly the naming of infrastructure is only one step in the broader reconciliation process. I certainly would not want to suggest that naming is a panacea or represents the entirety of what the city ought to be doing in terms of its reconciliation obligations,” said Nussbaum.

Zibi development controversy

The Zibi development has been a source of controversy with the Indigenous communities since 2013 when the developer, Windmill Development Group, proposed the construction of condominiums and commercial buildings on sacred Algonquin grounds at Chaudière and Albert Islands.

“We would never destroy a mosque or a church or a synagogue. Why is it OK to destroy a sacred island?” said Gehl.

The name Zibi means “river” in the Algonquin language and was suggested to Windmill by Patrick Henry of the Canadian Canoe Foundation, who is non-Indigenous. Dumont and Gehl have protested the Zibi development and agree that using the Algonquin word is a superficial offering from the developers.

“It was to appease or to bring on board or to signal that they cared about the Algonquins, when they really don’t, all they care about is development,” said Dumont.

Signage within the Zibi construction site is trilingual: English, French and the Algonquin language. When the development is finished, there will be Algonquin names for parks and streets and trilingual signage throughout the community.

In a statement from Zibi, they say the name is “a tribute to the traditional land of these First Nation Peoples, and a celebration of the waterways surrounding the development.”

Windmill and Dream Unlimited (the current development group in charge of Zibi) recognize that the development is on unceded Algonquin territory and have engaged the Indigenous communities throughout their design process. The Algonquin of Ontario organization as well as the Algonquin of Pikwàkanagàn have signed letters of intent with Dream, creating a partnership that is intended to preserve and promote the Algonquin culture, according to the Algonquins of Ontario website.

In a land that is trying to right the wrongs that started hundreds of year ago, some say a name is too small of a step towards reconciliation.

Gehl asks an important question: “Would you feel amended by having a street named after you and not having any of your land and resources back?”